In this chapter, we will first discuss some design and reuse principles of modularity in software design, and then introduce the modular design of the GoFrame framework to better understand the philosophy behind GoFrame's modular design.

I. What is a Module

A module, also known as a component, is a unit of encapsulation for reusable functionality within a software system. The concept of a module may vary slightly at different levels of software architecture. At the development framework level, a module is the smallest unit of encapsulation for a specific type of functional logic. In the Golang codebase, we can also refer to a package as a module.

II. Goals of Modularity

The purpose of modular design in software is to achieve as much decoupling and reuse of software functional logic as possible, with the ultimate goal of ensuring the efficiency and quality of software development and maintenance.

III. Principles of Module Reuse

REP Reuse/Release Equivalency Principle

The Reuse/Release Equivalency Principle (Reuse/Release Equivalency Principle): The smallest granularity of software reuse should be equivalent to the smallest granularity of its release.

In simple terms, if you want to reuse a piece of code, make it a separate module.

CCP Common Closure Principle

The Common Closure Principle (Common Closure Principle): Classes that are modified for the same purpose should be placed in the same module.

For most applications, the importance of maintainability far outweighs reusability. Code changes caused by the same reasons are best kept within the same module. If dispersed across multiple modules, the cost of development, submission, and deployment will increase.

CRP Common Reuse Principle

The Common Reuse Principle (Common Reuse Principle): Do not force a module to depend on things it does not need.

You might have experienced integrating module A, but module A depends on modules B and C. Even if you don't need modules B and C at all, you have to integrate them. This is because you're only using a portion of module A's capabilities, and the additional capabilities of module A bring extra dependencies. If following the Common Reuse Principle, you need to split A, retaining only the parts you need.

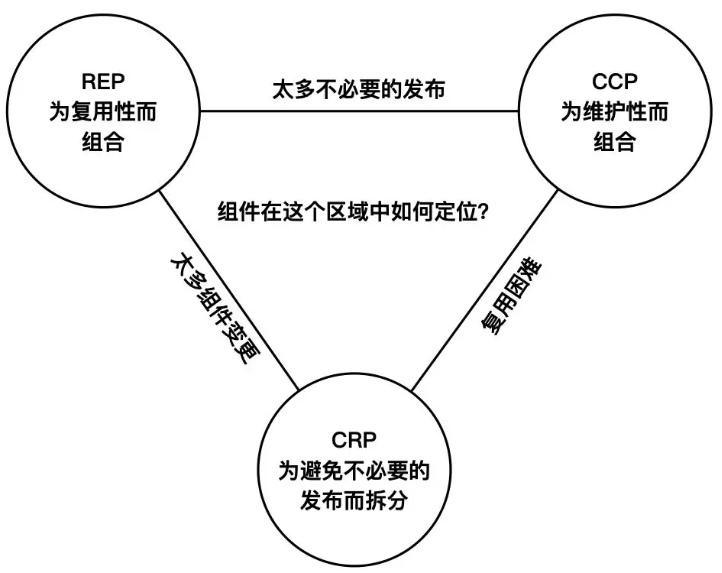

Competition Between Reuse Principles

There is a competition between the principles of REP, CCP, and CRP. REP and CCP are adhesive principles, which make modules larger, while CRP is an exclusive principle, which makes modules smaller. Adhering to REP and CCP while ignoring CRP will lead to dependencies on many unused modules and classes, resulting in your module undergoing too many unnecessary releases due to changes in these modules or classes; adhering to REP and CRP while ignoring CCP, because the modules are split too narrowly, a change request might require changing n modules, incurring significant costs.

Figure 2. Tension Diagram of Competition Between Module Reuse Principles

A competent architect should be able to locate the most suitable position within the tension triangle region for the current state of the development team. For example, in the early stages of a project, CCP is more important than REP, and as the project develops, this optimal position should be constantly adjusted.

IV. Framework Module Design

After the introduction of module design principles and reuse principles, we should have a general understanding of the principles of module development and management. Let's continue with the introduction of the framework's modular design, which will be relatively easy to understand.

Monorepo Package Design

According to the REP principle, we understand that a reusable module supports independent version management, and such is the case for monorepo package design. There are many such monorepo packages in Golang, where each package is an independent module. According to the CRP principle, a monorepo package can be further refined and decoupled. Let's take a scenario of developing complex business projects, with common package dependencies like this:

module business

go 1.16

require (

business.com/golang/strings v1.0.0

business.com/golang/config v1.15.0

business.com/golang/container v1.1.0

business.com/golang/encoding v1.2.0

business.com/golang/files v1.2.1

business.com/golang/cache v1.7.3

business.com/framework/utils v1.30.1

github.com/pkg/errors v0.9.0

github.com/goorm/orm v1.2.1

github.com/goredis/redis v1.7.4

github.com/gokafka/kafka v0.1.0

github.com/gometrics/metrics v0.3.5

github.com/gotracing/tracing v0.8.2

github.com/gohttp/http v1.18.1

github.com/google/grpc v1.16.1

github.com/smith/env v1.0.2

github.com/htbj/command v1.1.1

github.com/kmlevel1/pool v1.1.4

github.com/anolog/logging v1.16.2

github.com/bgses123/session v1.5.1

github.com/gomytmp/template v1.3.4

github.com/govalidation/validate v1.19.2

github.com/yetme1/goi18n v0.10.0

github.com/convman/convert v1.20.0

github.com/google/uuid v1.1.2

// ...

)

The module dependencies in the example are typical universal modules, commonly found in most business projects. The module addresses are fictional for demonstration purposes and may not actually exist.

For those who have developed slightly complex business projects using Golang, such scenarios should be familiar. A typical software company often has at least hundreds of such projects, and the real module dependency relationships are far more complex than those in the example. In Golang project development, maintaining module dependencies is a significant challenge, and we often encounter pain points, including:

- Numerous modules achieving the same functional logic, increasing selection cost

- Excessive module dependencies affecting a project's overall stability

- Excessive module dependencies causing confusion over whether to upgrade these modules

- Modules being scattered in design, lacking a unified structure. Refer to the section: Unified Framework Design

A case in point from personal experience.

My company has dozens of self-developed modules, widely used across hundreds of business projects. On one occasion, we submitted bug fixes for several modules, two of which were notably critical. Immediately after, we required all business projects to upgrade their corresponding module versions with utmost caution. Of course, this wasn't a one-time instance, and similar scenarios are easy to imagine.

Alternatively, we could choose not to actively push all business projects to upgrade modules; instead, projects only upgrade when encountering these bugs. Management's response to such a solution......is best imagined harmoniously.

The primary cause of such issues is often the instability of modules, which require continuous iterations and improvements. Projects using these modules are inherently coupled, and changes in these modules inevitably affect related projects. The more foundational a module is, the broader the dependency from top-layer modules and the greater the impact. But even if a module stabilizes, risks still exist. Golang's standard library, widely considered stable, is continually evolving with improvements and bug fixes—just fortunate not to encounter them—posing relatively low risk.

Good software design isn't static but capable of rapid adaptation to changes, allowing quick improvements. Module design and management are no different. Seeking ways to promptly refine module logic and effectively maintain module dependencies is more practical and efficient than merely developing more stable functional modules.

Module Aggregation Design

GoFrame's approach to modular management leans more towards the CCP principle, valuing maintainability more than reusability. Since GoFrame is considered from the perspective of development frameworks, the overall framework design is top-down rather than point-wise. As mentioned, foundational modules have a wider impact due to their extensive dependencies on top-level modules. Therefore, the framework maintains core universal modules collectively, ensuring closure and stability of foundational modules, enhancing development efficiency and maintainability, and reducing integration and maintenance costs through unified version management.

From the standpoint of GoFrame's modular design, the dependency scenario in the earlier example should resemble the following:

module business

go 1.16

require (

github.com/gogf/gf v1.16.0

github.com/goorm/orm v1.15.1

github.com/goredis/redis v1.7.4

github.com/gokafka/kafka v0.1.0

github.com/google/grpc v1.16.1

// ...

)

GoFrame maintains only common core modules, while non-core universal modules or those with high stability are still recommended to use as monorepo packages, as advocated by REP and CRP principles of module reuse. Under this design pattern:

- The framework's core maintains a comprehensive set of universal foundational modules, reducing the cost of choosing foundational modules.

- We only need to maintain a unified framework version, not dozens of module versions.

- We need to understand only one framework's changes, not changes across dozens of modules.

- Only one framework version requires upgrading, not multiple module versions.

- It reduces developers' cognitive load, enhances module maintainability, and makes maintaining module version consistency easier across projects.

V. Common FAQs

1. Although each module is designed with low coupling, even when modules can be selectively included, you still have to download the complete framework code.

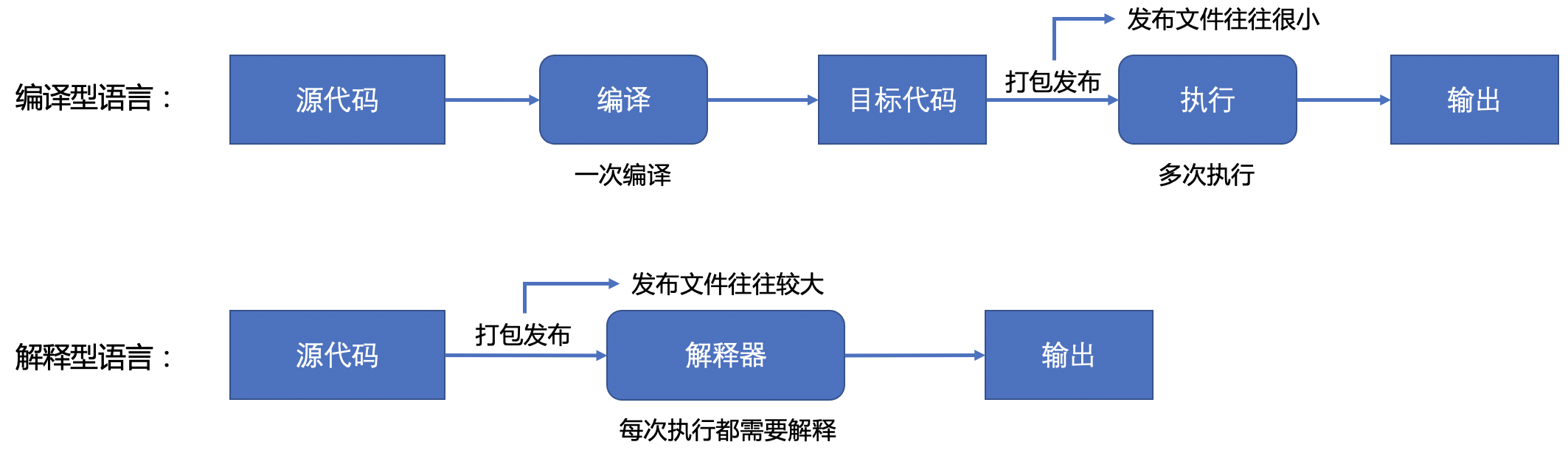

This is not an issue for compiled languages, as source file downloads at the file level are not directly related to logical coupling between modules. The root cause of this issue stems from differing perspectives on understanding compiled languages versus interpreted languages. In the internet age, interpreted languages have thrived, while Golang stands distinctively popular yet unique in this era.

- Compiled Languages: (taking static compilation as an example) typically start from the

mainpackage as the entry point. The compiler automatically analyzes the source code and compiles and processes resources of all logically dependent modules to ultimately generate static binary files for release. Source files, including those of dependent modules (logical dependencies), are used only during the compilation phase and are not directly relied upon for release, such as C/C++, Golang, Rust, etc. - Interpreted Languages: typically package their own source files (or bytecode) along with the source files (or bytecode) of dependent modules for release, e.g., PHP, Java, NodeJS, Python, etc. In this case, the size of dependent module source code significantly impacts project release. Furthermore, module dependencies encoded in package configuration files result in all specified modules being included during packaging, regardless of logical dependencies. If a module contains 100,000 functions and only one function is utilized, all functions within that module are packed for release, as interpreted languages do not undergo "compile-assemble-link" stages before deployment, requiring full parsing at runtime for both source code and module dependencies. Particularly for those transitioning from PHP/Java to Go, this mindset needs adaptation.

2. Will the release frequency of the framework increase if the version change of any module in the framework triggers a framework release?

Certainly, the module design of the framework considers stability factors, organizing only common core modules according to CCP and avoiding specific business logic encapsulations, as such implementations add variance to framework modules.

Under conditions ensuring a degree of stability, module version releases adhere to the framework's unified iterative development schedule. Aside from necessary hot fixes, version releases happen in fixed time windows to ensure the core framework's stability. Therefore, managing module versions via aggregation does not increase the release frequency of the framework; rather, it decreases it, making module versions within the framework more stable.

3. The framework aggregates and maintains core universal modules; what constitutes a core universal module?

First, they are foundational modules, typically residing at the lowest level of the module dependency chain and having the greatest stability impact on projects.

Second, the vast majority of projects (the 80-20 rule) would rely on common foundational modules, which can be considered core modules.

Finally, these modules do not encompass specific business logic implementations. Counter-examples include modules related to WeChat official accounts/weapp, CMS/CRM, blockchain, etc., which are specific business logic packages.

A fully accurate assessment of module universality is unattainable. To keep the core concise, the framework adopts a conservative stance and iteratively adjusts based on actual needs.

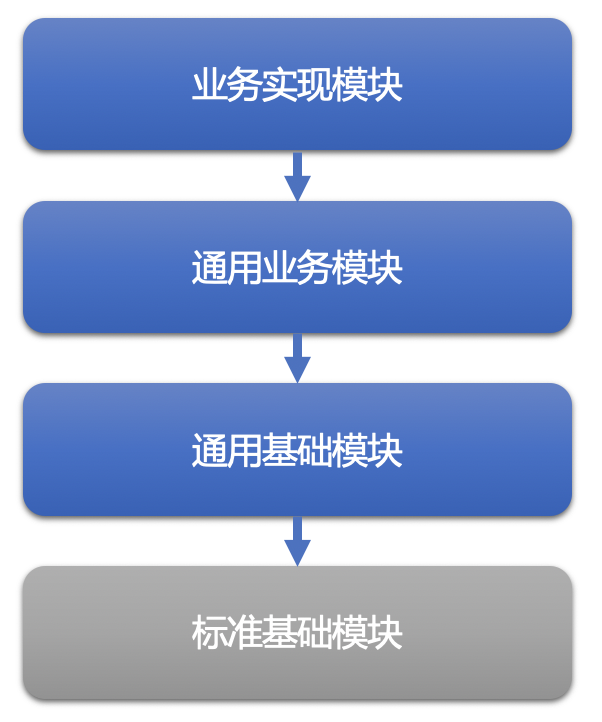

Here is a reference for module layering:

Reference for Module Layering

Business Implementation Modules: Logic implementation for specific business projects, including further code layering of the business project.

Common Business Modules: Reusable business logic encapsulations, e.g., WeChat official accounts/weapp, CMS/CRM, blockchain-related logic encapsulation modules.

Universal Base Modules: Foundational modules not provided or extended based on the standard library, such as configuration, validation, caching, ORM, I18N, etc.

Standard Base Modules: Golang's standard library.

4. Since the framework includes many modules, with limited human resources, I believe each module couldn't be better than individual single-package projects on GitHub.

Doing something less frequently doesn't inherently ensure better quality; there's no direct causality between the two.

5. Because the framework includes numerous modules, I think the performance of each module is generally not high.

Haha.